Chapter 2

FARMING

INDEX

FARMING IN THE VALLEY

THE FARMER'S YEAR

FARMER FRED

WOMEN'S WORK

WEATHER

DAMSONS

PEAT

GRAZING ON THE MOSS ROADS

HUNTING SHOOTING AND FISHING

FARMING IN THE VALLEY

Tom Airey, a farmer born and bred

People have lived in the valley for thousands of years. Evidence of this occupation was first found in 1877 when a Neolithic arrowhead and stone celt were unearthed. Then at Stakes Moss, in 1895, whilst digging for peat, a bronze spearhead was found. Once the valley was covered with forest. This was cleared to prevent the Scottish raiders using it for cover as they pillaged the valley for stock.

At first all the land was held in common. Geese, sheep, pigs, cattle and horses were all kept on the Common Land. The valley was vastly overgrazed. Later came the Enclosures Acts and the valley was divided mainly amongst the big landowners.

During the Second World War years food production became an absolute priority and most farms were obliged to grow food crops by law. To help in this operation a Government body, called the Agricultural Committee, was set up. Mr Brooks at the Cragg looked after it. It consisted of groups of men who went round the district ploughing, threshing and bindering. Often these units were self-contained, pulling their own fuel supply. These were basically two forty-gallon drums of fuel on wheels with a hand pump at the front to pump it into the tractor tank. Land Army girls were also common on farms as were Italian and German POWs, who were transported to help with work from Bela River Camp, near Milnthorpe.

THE FARMER'S YEAR

JANUARY

The cows and young stock are inside.

Trade in fresh meat suffered when cheaper imports followed the invention of refrigeration in the 1920s. However, tuberculin testing and the accreditation of herds in the 1960s meant that the milk trade improved.

Cows and heifers were taken to Mirk Howe, where the shorthorn bulls of Jack Moffatt and Fred Hodgson serviced them for a fee. During the early part of the Second World War, their herd became accredited (tuberculin tested), so that any stock not accredited had to be taken to the bull at Tarnside until, six months later, all the herds were accredited.

Cattle feeding stuffs permit

The shorthorn cows were milked by hand. Later bucket (unit) milking machines were introduced, followed by pipelines and then milking parlours. The milk was cooled by standing the churns in cold water.

Later came surface coolers and in-churn coolers. Nowadays milk is cooled by refrigerated bulk tanks. The Milk Marketing Board was set up to purchase all the milk. Libbys built a factory in Milnthorpe to process it. Farming then became more prosperous. Haulage contractors R. Hodgson and later K. Fell were employed to transport the churns. Each farm had its own numbered churns, which were collected from stands on the roadside. Most farms milked between 10 and 20 animals. The cows were fed as much as 20lbs of hay, per day, during the winter months.

This was supplemented by kale, turnips, mangolds and crushed oats.

Dockrays, Jordans, Lunesdale Farmers, and West Cumberland Farmers' Provender Merchants and others supplied cattle cake.

Butter making certificate

Some of the milk was made into butter; cream was separated and churned by hand. The cream was kept in the cream pot and the skimmed milk fed to the calves. There was one churning each week, when butter was made. The cream was churned and weighed into pounds, put through a butter press, to extract most of the water and squared into butter pats, ready for sale. The buttermilk was fed to the pigs.

The farmers’ wives would walk, with basket on arm, to sell their produce in Kendal and Windermere. Ducks were taken, to be sold in Bowness. Eggs, vegetables and fruit in season, especially blackcurrants and strawberries also went to Kendal Market.

In addition to the skimmed milk, calves were also fed on hay and gruel mixed with hot water, from a bucket. Cows were tied by cow bands, in the shippons and were mostly “underhoused”, i.e. under the hay barn and had to be let out daily to a water supply, usually a spring, pump or well. Piped water arrived in the valley in 1948, so most farmers were able to install water bowls for the cattle to drink from. In the 1970s cubicle stalls were erected, with the help of Government Grants.

Silo buildings have gone through different stages. The first silos were concrete towers and had to be filled and emptied by hand. Then pits were made, by excavating the ground. The grass was loaded onto trailers with a greencrop loader, then buckraked onto the pit. Later, concrete lined buildings were used, where the cows could help themselves to the silage. More recently big bales, wrapped in black plastic, have become popular.

Most farms had free-range hens. Next came deep litter and battery farming. Eggs were collected weekly by Lunesdale Farmers and Express Dairies, from Appleby.

Granny Airey making butter at Mireside

Disease in animals has caused great anxiety to farmers. Boons, on the corner of Market Square, Kendal, was the farmers’ chemist. Cattle were treated with the ancient remedy of “need fire”, where they were driven through the smoke created by the fire, or over the hot embers, in the case of foot disease. One farmer from Crosthwaite remembers being asked by his brother to go to Endmoor, to help with a sheep, which he thought had foot rot disease. He duly went, unaware that it was foot and mouth disease, helped with the treatment and returned to his own farm. The stricken animal recovered and the disease did not spread to his farm! There was a case of anthrax at Esp Ford at the beginning of the 20th century. The carcasses were burned and the disease was halted. In the more recent outbreak of foot and mouth disease in 2001, farmers suffered all the restrictions of farmers throughout the country, but fortunately, the disease did not reach the valley.

FEBRUARY

Killing the pig

Jim Airey feeding the pig

This was the month for pig killing. Most farms kept two pigs for a supply of bacon and lard. Pigs were supposed to be killed, only if there was an R in the month. They were killed on a rota basis so that, in the absence of freezers, neighbouring farms could swap pork and liver etc.

This gave them a supply of meat over a good few weeks.

Pig killing day was quite an ordeal. Kit Simpson, Jim Bracken and Ted Inman all had humane killing guns, so one of them would be booked to go to the farm on a particular day. The washing boiler had to be full and boiling. The pig was led from the sty and walked alongside a pig creel. It was shot and had its throat cut. The blood was collected in a bucket, stirred all the time, to prevent clotting. This was used for making black puddings.

Killing the pig

Frances Mary Cartmell's list of fruit trees

planted at High Cartmell Fold

Hot water was then poured over the pig’s body and, by using special scrapers, the hair was removed. Next the body was raised, by the hind legs with a block and tackle. The insides were removed. The heart and lungs were collected in dishes. Black puddings were made from the blood, mixed with fat, herbs and oats. The intestines were cleaned and used for the cases. The bladder was usually dried, blown up and used as a football. A potato was placed in the pig’s mouth, to allow drainage of the carcass. Two days later the carcass was cut up. The head was used for brawn, the feet, pigs’ trotters, were boiled and eaten with toast, the rest, shoulders, flitches and pigs’ cheeks were placed in salt to cure.

The stomach was cut into little pieces to make a pig-belly pasty.

Anything else was eaten as pork. It was said that, the only thing not used on a pig was its squeal! If the sow was a “brim in” or in season (its temperature was up), the whole operation had to be cancelled.

MARCH

Ploughing and Lambing

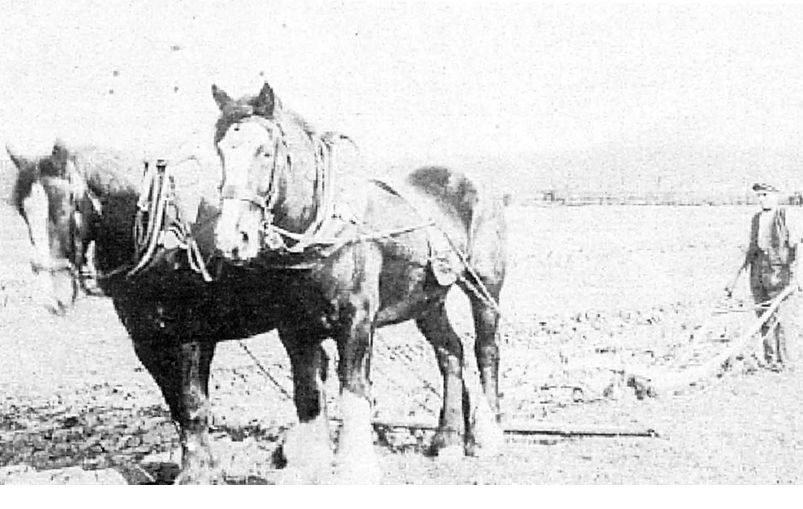

March was the time for ploughing and sowing the corn seed.

The rotation of crops from grass, to corn, to greencrop, to corn and back to grass, made ploughing an annual chore. When a field was ploughed out of grass, it was known as “leigh ploughing” and after a corn crop, “rigging up”. The first ploughs were made of wood, later of iron. Some of these were known as Stainton ploughs and pulled by two horses. A pair of horses and a ploughman could plough an acre per day. Later, ploughs had a wheel at the front, making the job easier.

With the introduction of tractors, which replaced the team of horses, came the Fordson drag ploughs. These ploughed two furrows at a time.

The next development was when the little grey “Fergie” appeared in the valley. Ferguson introduced hydraulically mounted ploughs, which Hoggarths of Kendal supplied.

The ploughman took great pride in his work. The art was to make straight furrows of equal size, which led to competition and ploughing matches were held locally.

Most farms had small flocks of “mule” sheep (a cross between Dalesbred and Teeswater tup), which were mated with a Suffolk tup, to produce fat lambs for Kendal Market. The Fatstock Marketing Corporation was formed and lorry loads of lambs were collected from the farms. Each lamb had to have a metal tag put in its ear with a number for identification purposes. Swifts of Kendal Abattoir also purchased animals for slaughter.

Tommy and Harry Walling transported other people’s stock to market, the abattoir or anywhere they needed taking. In 1980 they took three Friesian steers to market for John Wilson and a record cheque of £1,000 was received! Occasionally a lamb would be killed for the table.

The head was well cooked; the meat stripped of the bone and pressed to be sliced and eaten cold; even the tongue was used in this way.

Ploughing a grass field

John Wilson stitching up green crop with his daughter Minnie

APRIL

Cows let out, fencing and sowing crops.

Farmers sowed their green crop and made sure that they were on straight ridges (locally known as stitches).

They kept the furrows clean and weed free.

One farmer rang his neighbour at lunchtime, in an agitated state, saying that their stock had got mixed up.

The farmer sent his men round, post-haste, only to find that it was the seagulls that had flown from one man’s ploughed field to his neighbour’s! Fencing can either mean, improving hedges by means of laying, or erecting posts, rails or wire. Hedge laying is a skill, gained by practice and it is carried out when the leaves have fallen. The aim is to make a stockproof fence out of the material within the hedge, which will regenerate and last for years. The best results occur when a large proportion of the material is thorn. Styles differ in that some districts have soil cops, others plait the twigs along the top, whilst most areas stake newly layed hedges at frequent intervals.

Post and rail or wire fences now use tanalised material. The local treatment plant is at Dallam Tower. Years ago, posts were obtained from coppicing on Whitbarrow.

Violet Newcombe, Joyce & Irene Rockliffe, Joan Wood, Susan & Wendy Hayton making a bit of pocket money selling daffodils

Ted Inman letting his cows out

Empty, state-of-the-art cow stalls, 1938

Ernie Shepherd with his father,

Ernie, laying a hedge

Joe Park and John Myers

loading a peat barrow

MAY

Peat digging, green-crop thinning and weeding.

(described in the section on peat)

JUNE

Clipping and dipping sheep

Sheep in the lowlands were usually clipped of their fleeces in the months of May and June. Farmers preferred to clip before haymaking and silaging. Horned sheep on the fells were often clipped later. The fleeces had to rise, whilst they were still attached to the sheep, to make shearing easier.

In years gone by, sheep were washed by immersing them in a stream, before shearing them with hand shears. The wool was very much in demand, often making enough money to pay for the winter feed bill.

Ted Inman and his son, Edward, washing sheep, prior to clipping at Esp Ford 1920s

Richard Gardner sorting sheep for clipping at Tarnside Farm 1938

John Myers, Geoff Wills and Jack Myers shearing with electric shears at Durham Bridge Farm

Today, shearing is mostly done by mechanical shears operated by travelling gangs. Wool is no longer profitable.

Different areas had different styles of handling the sheep, whilst clipping. Some used a “kreel” (a type of platform), others an old carpet.

Nowadays, shearers have sophisticated trailers to make the job easier. If the sheep was not handled properly, during clipping, internal organs could be twisted, resulting in the death of the animal. To remedy this, the sheep was immersed in water.

After shearing, the fleeces were wrapped up in a wool sheet, ready for collection, by Pickles of Kendal. Now the collecting is done by Wool Growers of Carnforth.

After clipping, the sheep were usually dipped in a liquid to repel blow strike by flies. Later on in the year, in the autumn, they would be dipped again to combat sheep scab.

Richard Gardner hand clipping

Dipping used to be compulsory. Papers had to be obtained from the police station. One form was filled in with the date and time of the intended dip, the other had to be completed once the dip was done. A policeman could attend the dipping, to make sure that each animal was fully immersed for the recommended time, usually three minutes. Some of the original dipping tubs required the operators to lift the sheep, by hand, holding it under the liquid for the required time. Later swim-baths were introduced, where the animal swam through the dip. Nowadays spray booths are used. Dipping now requires operators to attend a training course and be awarded a certificate before they can use and dispose of soiled dip.

As well as using local fleeces, wool was imported to be spun, as it was helped by the damp climate. There is a spinning gallery at Pool Bank, which was also used to spin flax. There is also evidence of one at Cartmell Fold.

JULY

Haytime

Cutting grass for hay

Fred Whitwell with Sheila

and Dolly at 4.15am

Bringing in the hay was very hard work years ago. It was cut by finger mowers, pulled by horses. The farmers would get up at four in the morning to cut, before the heat of the day. At this time, the cleggs weren’t biting the horses. The swathes were turned by hand, with a rake. When the hay was nearly “cured”, it was put into “cocks” (heaps of hay), so that the wind could blow through it. This also prevented the hay from spoiling, if it rained. The hay was then taken into the barns, with carts adapted with hay shelvings, so that they could carry a bigger load of hay.

Gardner family collecting

hay in School Meadow

John Wilson of Yews rowing

up hay by hand

The real breakthrough came with the invention of the mower, behind the tractor, and then the drum-mower. The introduction of the pick-up baler was another step forward. Bob Jackson, a contractor, was the first man to buy one. It was difficult to get hold of him, as everyone required him at the same time. Joe Walker from Michael Yeat had his own rotary baler. The introduction of silage eased the pressure a little, because the farmer was not as dependent on the weather. Still, people work long hours, especially at this time of the year.

AUGUST

Bringing in the peat and the corn

The peats were worked to get them dry and housed in the peat sheds.

The corn was cut during August. In 1887, the Westmorland Gazette reported an early harvest. On August 1st, Mr Thomas Bentham of Flodder, cut his 6 acre field of oats. Two days earlier, Mr Harrison of Low Levens had done the same. Oats were the most important grain grown in the area.

Ted Inman and his son, Edward, thatching corn ricks

Gardner family harvesting the corn and wheat in the 1920s

Shepherd family harvesting at Broad Oak

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER

Damson picking, turnip and mangolds to pull, potato picking.

Schoolchildren could get a special card to release them from school to pick potatoes. Pulling mangolds and turnips on frosty days was not a pleasant occupation! (Damson picking is described in the section on damsons.) After the damson harvest came bracken time, when bracken was cut and carted on sledges, down the steep slopes, into the valley. Next the sledges were yoked to a horse and pulled across the meadows to the barns, to be used as winter bedding for stock. Mountain ash berries were collected for poultry food. Hazel nutting on Whitbarrow was enjoyed during this month.

Rowley Mason and his father harvesting apples

Herbert Park picking damsons

Transporting turnips by steam traction engine at Long Garth, Lyth

Herbert Park storing winter fuel at Dawson Fold

NOVEMBER

Threshing at Beck Yeats

(J.Hardman)

Alan Jackson and his father

dry-stone walling at Row Farm

Hedging and ditching

Farmers maintained their hedges and ditches in November (see April). On threshing days, competitions were held to see who could lift the most. They were very happy occasions, dusty too! Health and Safety would have a Boon Day now!

DECEMBER

Muck carting and spreading. Woodcutting.

Grandad John Gardner

chopping sticks for kindling

Tommy Thornburrow and John Gardner

carting wood to Gregg Hall in 1940

The cows were brought in during December, so the muck had to be lifted and carted, by hand. Often there would be competitions between men, as to who could spread the most heaps.

One farmer, who was very keen on talking, loaded his cart with manure, met the roadman, who purposely kept him talking, until lunchtime. The farmer dare not be late for lunch, so he returned to the farm, with his horse-cart still full of manure! Woodcutting and logging was a wet day job. The wood was sawn with a “bushman” and sawhorse.

Geese were taken to Kendal Market, the Saturday before Christmas.

Holly was sold to Powell’s shop on Highgate Bank, Kendal.

FARMER FRED

Asturdy man is farmer Fred,

With weathered face and sturdy tread,

His whistle shrill beyond the hill

Calls Gyp and Jill

to do his will And bring the sheep to fold.

His voice is deep,

His heart is kind,

He has a sweet, contented mind.

Among his flock in pastures green

Or flower starred meadows green,

With faith serene and

skill supreme

He labours through each day.

His stock he feeds

Their daily needs,

His foremost thought always.

For helpfulness,

In strain or stress,

This land knows not his compare.

He lends a hand, whate’er demand,

Nor grudges time to spare.

By worldly standards, he’s not rich,

He flaunts no flashy car,

No pleasure yacht

But what he’s got o’ershadows these by far.

A heart that’s kind,

a contented

mind,

His farm is his guiding star.

He lifts his eyes to read the skies.

He needs no isobar.God grant him health,

Strength and success

And crown his life with happiness.

Miss Bibby

Miss Bibby was a single lady who ran a private school in London during the Second World War. She adopted two of her pupils who were orphaned in the Blitz. One child became a paediatrician, the other an opera singer in Italy. She wrote this poem while ill in bed, listening to Fred working with his sheep outside. She owned Ghyll Head Farm with another friend. Her favourite saying was “The hardest ship to sail is a partnership”.

WOMEN’S WORK

Les Park and his sisters, Frances and Freda,

mixing calf food with Mum

The farmer’s wife has always had a very hard life. As late as early 20th century she wore clogs and a rough “brat” (apron made out of sacking, with tapes attached) and she would have to rise very early to have breakfast ready for the menfolk, usually havermeal porridge with skimmed milk.

Washday was particularly strenuous. The fire had to be made under the washing boiler.

All the garments, which needed to be hand washed, were scrubbed with blocks of Fairy soap. Dolly tubs were also used, rotating the dolly legs in the tub and using dolly blue to brighten the whites.

Water was drained from the clothes, using a hand operated mangle. Irons were heated in the fire and then fitted into a slipper, to press the garments.

Baking was an all day task. Bread for the whole week was made in a fireside oven, after waiting for the dough to rise in front of the fire. Butter had to be made in hand-operated churns. It was then taken to market.

Before the advent of modern conveniences, such as vacuum cleaners, floors had to be scrubbed on hands and knees. Dusting was done with goose wings. Evenings were spent sewing or pegging rag rugs, by candle, rush or oil lamplight. At hay time, as well as providing meals for all the field workers, farmers’ wives were expected to help with the jinny raking.

One of her many other jobs was to make the feather mattresses and pillows. When the poultry was plucked, all the feathers were put into the boiler to be cleaned. The sharp quills were cut off by hand and the feathers put into the casing, to make the mattress, eiderdown or pillows.

Finally they had to be hung on a line to dry. Nellie Berry recounts that her father insisted that the feathers were stirred in a dry boiler, heated by a fire below.

On top of all these chores, women were often responsible for feeding the calves, hens and Christmas poultry. Needless to say, they were usually bringing up large families of children, alongside all the house and farm work! Despite all the changes to life, which we enjoy in the 21st century, few would deny that the farmer’s wife still has a most demanding role to play.

Farming is enjoyable... but so tiring. Bait time in the field, Gardner family

Sally Inman making a feather bed

Feeding hens at the Row

Joan Walling delivering milk to the bungalow at Strickland Tenement

WEATHER

The proximity of the Lyth Valley to Morecambe Bay, the prevailing south-westerly winds and the Gulf Stream, ensures that it enjoys a gentler climate than the rest of the Lake District. This does not mean that it has not suffered extremes of weather, over the years.

The valley flooded most winters, especially before the drainage ditches were improved

Floods at harvest time, 1920s

Foulshaw Lane - sea defence breached 2002

The dyke repaired as soon as the floods receded

Floods were a common occurrence during the winter months, especially prior to the installation of the drainage pumps. In 1927, there were gales and floods at harvest time, ruining the grain at Mireside, which certainly lived up to its name! Recently the valley had severe flooding in 1999 and 2002, when the river broke its banks. Rainfall in the valley has been recorded by local amateur meteorologists, H. A. Wilson in Levens, Grenville Howes in the Howe, Rodney Sale and Peter McDonald in Crosthwaite. Average annual rainfall over the four years from 1998 to 2001 is: Levens 49 inches, The Howe 61 inches and Crosthwaite 57 inches.

High gale-strength winds often caused

damage to trees. In November 1984, a single

branch from an ash tree damaged a caravan,

mobile workshop and a Fiesta car. Jim Bownass

had been away for the day and knew nothing of

the gale until he returned home to find this wreckage.

Winds, usually from the west, have caused damage. In 1756 a beech tree came down at the High, in a hurricane. A single branch measured 193 feet. More recently in the 1950s a brick built workshop at Bridge End was demolished and a tree came down onto Jim Bownass’ mobile workshop in 1984. In the spring, the wind can move round to the east and stay there for a few weeks. This can be a cold, drying wind, known locally as the “helm wind”.

Heavy, disruptive falls of snow have been recorded. In 1924, with the snow knee deep, the children were sent home from school early. Some people remember the snows of 1947, when the valley had its heaviest snowfall of the 20th century. Several roads were impassable. The photograph below shows how deep it really was! On the 23rd February 1994, snow 26 inches deep was measured at Crosthwaite.

Severe frosts have also been recorded. In 1963, it froze every night for seven weeks and Lake Windemere was covered in ice. Many domestic water pipes froze. John Stott, contractor of Crosscrake, was kept busy trying to thaw them by passing heat along galvanised piping with his welder. Farmers had big problems with the diesel in their tractors waxing.

A summer drought occurred in 1818. Another year of note was 1889, when there was a prolonged drought. It was reported, in the Westmorland Gazette, that hundreds of red squirrels died through lack of water. 1976 was a more recent example of drought.

Pockets of ice on the mosses

Worst snow of the century, January 1947

Snow up to 26 inches deep in places, 1994 at Hollow Clue

Snow at blossom time

WEATHER SAYINGS

Snow at Farley Cottage

Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight.

Red sky in the morning, shepherd’s warning.

Another version:-

Red sky at night, a sailor’s delight, provided the wind be westerly,

Red sky in the morning, sailor’s warning.

The cock crows on going to bed,

It rises with a watery head.

If it rains at flow, go and mow.

If it rains at ebb, go to bed.

If you could hear trains crossing the viaduct at Arnside, bad weather

would be expected.

If you could hear trains at Oxenholme,

fine weather could be expected.

As the days get longer, the cold gets stronger.

Drought-extract from the Westmorland

Gazette, August 1889

A mackerel sky means that it will rain within 24 hours.

Rain before seven, fine before eleven.

Mist rises in sops, comes down in drops.

Three white rags (white hoar frost), then rain.

If the oak is out before the ash, we can expect a splash.

If the ash is out before the oak,

we can expect a soak.

If the Lakeland hills look near, the weather will worsen.

If the hills look distant, expect

fine weather.

DAMSONS

Crosthwaite, early 20th Century - Mr. Millard's

newly planted orchard at Dodds Howe (top left)

(J.Hardman)

Damsons have been grown in the Lyth Valley and surrounding districts for generations. No one knows exactly where they came from but several theories have been put forward. One of these is, that the monks from the Furness area introduced them. Another is, that they come from the wild plum or bullace. Some people believe that the Crusaders brought them back from Damascus. Damsons were also well known to the Romans. Damson trees can still be found near Roman, archaeological sites. There may be some truth in all the above beliefs. One thing is certain, the Lyth Valley damson is quite unique. It has a distinctive flavour and shape, which differs slightly from orchard to orchard, depending on the soil type.

Hartley Trotter junior selling

damsons in Kendal Market

In the past, the money from selling damsons was an important part of a farmer’s income. The older generation used to say that damson money was rent money. During the war years they were much in demand, as imported fruit was scarce.

At first, fruit was transported to the local markets in Kendal, Ulverston and Milnthorpe by horse and cart. With the arrival of the steam train, opportunities arose for selling the fruit further afield. One buyer placed an advert in the Gazette in 1875, asking for damsons at a price of 6/6d to 7/0d per score (twenty pounds). In the Westmorland Gazette, of December 1949, it was reported that James Inman carted damsons to Sandside Goods Yard. His truck was Number 46 out of 80.

With the arrival of motor transport, buyers came from the large industrial towns: Emsleys and Collins from Bradford, Bentleys from Colne, Mackies from Manchester, Naylors from Leyland, also Hopkinsons of Bradford, and Hills of Waterfoot. These companies sold tons of damsons to markets and preserve manufacturers.

Prices have varied over the years from 18 shillings per score in 1964 to £8 in 2001.

Damsons need very little management. The blossom usually flowers in the second half of April. The fruit is ready for picking in early September. Enemies of the damson are frost at blossom time, a grub, which eats the stone of the newly set fruit and lately a virus, leaving the fruit resembling a banana in shape.

Before people could get income support, pickers were numerous. Workers would take a holiday to coincide with fruit picking time. Competitions for who could pick the most in a day were common. Many pickers could total 20 to 30 score per day.

Today, most damsons are sold in small quantities and are used for more varied purposes, for freezing, ice-cream (English Lakes Ice Cream), jam, pickles, beer, wine and more recently damson gin. Cowmire Hall has a small business, making damson gin for sale both locally and at the prestigious London store, Fortnum and Mason.

Damson orchards up until the 1950s were kept in a commercial fashion. Fallen trees were replaced in the autumn with new ones, recovered from hedgerows. They were staked and surrounded with thorns to protect them from cattle, sheep and deer. In 1935, Malcolm Hughes did one of the last full orchard plantings for Harold Millard at Dodds Howe. Mr Millard set up the Kendal & District Damson Association in 1939, to help local growers to sell their fruit. For a brief time a small factory operated in Levens, making jam. It closed because of the shortage of both pickers and sugar during the War. The Association itself only lasted a few years.

More recently, the Westmorland Damson Association, set up by Peter Cartmell in 1996, aims to encourage the regeneration of local damson orchards. Newspaper articles, radio broadcasts and a piece in the BBCs Country File have made everyone more aware of this delicious fruit.

Damson Day, held each year around blossom time, gives us all a chance to celebrate the fruit in all its forms.

Sending damsons to the jam manufacturers

A family affair - the Youngs and Dixons from Moss Side

John and Ivy Wilson from Yews, selling damsons at the roadside

Mr. Millard's damson orchard in bloom with Margaret Armstrong in the foreground

RECIPE FOR DAMSON GIN

1 Pound Damsons

1 Pound Sugar

1 Bottle Gin

If you like a darker richer, liqueur use 3 pounds of damsons and 2 pounds of sugar.

Prick the damson skins and place in a glass toffee jar. If you are using frozen damsons this may not be necessary as the freezing process breaks down the fruit. Add the sugar and gin and seal tightly. Agitate daily until all the sugar has been dissolved. Leave to mature until Christmas.

Remove the stones from the damsons and roll in melted chocolate for a delicious Christmas treat.

THE DAMSON TREE

Picking damsons in Mr. Millard's orchard,

Bob and May Armstrong

There is a tree which grows around,

In hedgerows it used

to abound,

Planted in orchards in profuse

It produces fruit for folks to use.

It is the damson growing here

In Crosthwaite, Lyth and in Brigsteer,

Underbarrow, Levens,

Witherslack as well,

And across the River Winster in Cartmel Fell.

Cross Bowland Bridge along we stride,

Go up a lane past Borderside

Where we have heard in

days of yore

William Pearson planted trees galore.

And up the lane past Roper Ford,

Past Brown Horse Inn on the Winster road.

For damson trees there’s not a lot

But we’ll

go as far as Barker Knott.

So we turn round and pass High Mill

And then we turn and climb a hill

And on our way we see

Knipe Tarn

Then down to Crook and Latterbarrow Farm.

Here we are in a lovely valley green

Where lots of orchards used to be seen.

We pass a place called Thorney Field

Where Bramley apples

used to yield.

And down the Gilpin Beck we go

Then past Crook Foot where pear trees grow,

On to Starnthwaite

hamlet and Crosthwaite Green.

Lots of damsons here to be seen.

These trees are lovely in the spring,

All pearly white when blossoming,

And later on the

leaf appears,

They’ve done that now for years and years.

But in September, that’s the time,

The fruit is picked, it’s just sublime,

Then

sold by roadside, out of vans

In markets, shops, then popped in pans.

They are such a useful fruit to cook.

For making jam go by the book,

Make pasties, pies, stews

quite fine,

Can bottle, freeze, makes lovely wine.

Makes puree, pickle. Is that the lot?

They are eaten ripe from the tree top.

And what about just mentioning

A heavenly glassful of

damson gin?

And so before it gets too late

Let’s plant some trees for old time’s

sake

And then we will all be forgiven,

We will fulfil an old tradition.

John Wilson, 25th April 1996 (Yews)

PEAT

Edgar and Clara Park, at South Low Farm,

cutting peat, using special tools and cart

Peat is formed, over centuries, from decayed and partially carbonized vegetable matter, in a similar way to coal. The Lyth Valley sphagnum moss and the boggy nature of the ground made ideal conditions for its formation after the Ice Age.

Peat has been used for centuries as a fuel, either on its own, or with wood. Kendal was the main market for the peat. In the last century carts, accompanied by clay pipe-smoking women, trundled over the hill to the town, up to 25 of them a day.

Most people in the valley had a “peat right”, an area of ground where they were able to dig the peat, for use in their homes. They had grates, specially built for burning peat, with a reduced draught. The fires were kept in all year round. The smell of peat burning is one never to be forgotten, especially when accompanied by crickets and cockroaches on the hearth!

Spring was the season for cutting the peat. The spade was wooden, edged with metal. The cutter would remove the top 30 cms of peat, known as “fey”, and discard it. The next layer was cut into a block, 15 cms square and 6 cms deep, called “grey peat”. The layer underneath this was the “black peat”, the best quality and much harder and, when burned, produced more heat.

Peat stacked in piles to let the wind blow through it

After cutting, the peats were loaded onto a special barrow, with a large, flat wheel at the front, designed to prevent it from sinking in the bog. They were taken to the “drying grounds” and laid on their sides in “wind rows”. It took 5 to 6 weeks of summer sun and wind to dry the peats out. Next, they were put in wooden framed peat sheds, roofed in corrugated iron. Finally, they were taken by cart, with special shelvings, to the peat shed at the homestead.

Edgar Park, with his son Colin,

and his Little Grey Fergie,

bringing in the peats

Stories from the peat mosses are many; there was the farmer, who suspecting his peats were being stolen, white-washed them, only to find them burning on his neighbour’s fire; the carter, Heinz, a German POW, whose horse dropped dead, between the traces, on Howe Lane; the tank, which sank in the mosses during the Second World War; also, a tractor belonging to the Scotts at Matson Ground, which got stuck in the peat; the couple, Roger and Aggie Atkinson, as reported in the Westmorland Gazette, who were killed by lightning on Foulshaw Moss, in 1812. In the 1930s the peat mosses caught fire. The air was black with smoke for weeks on end.

The trade in peat declined with the coming of canal transport and the railways, which brought cheap Lancashire coal to the area. Edgar Park, of South Low Farm, was the last person to cut peats in the valley, although cutters are still operating on Witherslack mosses.

GRAZING ON THE MOSS ROADS

The letting, for grazing, of the moss roads probably started after the 1815 Heversham Award, which followed the Enclosures Acts. This was when the mosses were drained and the land divided into fields. The green roads gave access to the land and to the drainage system. The tracks, between the fields, had strips of grass along the sides and gates at each end, looking much as they do today.

The letting of the Moss Roads

The Lyth Roads Committee was set up to look after the roads and to auction the grazing rights. The farmers, having land in the moss area, would take part in a candle auction each year in a local inn.

The auction proceeded as follows - a candle was set to burn with a pin stuck into it, an inch from the top. Farmers bidding for the right to graze their animals, along the wide grass verges, would call out their bids, as the candle burnt down. The person to make the last bid, before the pin fell, was the one to win the auction.

Nowadays, farmers who own land on the mosses, can still bid for grazing rights on moss roads at a special auction held each year in April. Interested parties gather at the Lyth Valley Hotel, where the chairman Derek Cleasby is the auctioneer. Gordon Pitt is the secretary and Colin Park the timekeeper. Farmers have a minute to bid. After 30 seconds, the timekeeper shouts out “Half-time”. A bidder has to have shouted out his bid in the first minute. If someone else bids, within the minute, the bidding goes into a second minute. This continues minute by minute until there is only one bid within the minute. The timekeeper then shouts “Time” and the next lot is put up for auction.

Money from the sale of annual grazing rights is used for the repair of these roads, the fences and cattle grids and, not least, for refreshments on the auction night! Rents are due on the 11th November. Grazing rights cover the period 20th April to 11th November. The rules require that thistles and rubbish should be cut and cleared in July and that no nitrogenous fertiliser be used. Fines are imposed for breaking the rules.

HUNTING, SHOOTING AND FISHING

The Rabbit Clearance Society was started in 1958 by the Ministry of Agriculture. It was one of 250 such groups across the country. The Society was under the chairmanship of the Earl of Lonsdale, Jim Bell of Fellside was appointed as the secretary and several local farmers and landowners were elected to the Committee. Their aim was to control the ever-increasing rabbit population.

Funds were raised by charging interested farmers on a per acre basis, depending on whether it was grass and crops or rough fell and woodland. When the Society was first started, every pound raised in subscriptions was matched by a pound from the Ministry.

Cecil Walling from Gilpin Bridge was appointed as the man to do the job.

He rode a motorcycle with sidecar, to carry the tools of his trade. One working day thieves stole his gun from the sidecar! At first he covered many acres and did a splendid job, keeping rabbit numbers down. Two thousand were caught in the first year. However, sadly, with the advent of myxomatosis, rabbits became scarcer.

The Society turned their attention to other pests, which farmers needed to control. The number one enemy was the mink which had bred in the wild after escaping from mink farms, where it was raised for its fur. It is an animal which can both swim and climb trees. It has no natural enemies in this country and is a vicious killer. Apart from preying on otters, fish and birds’ nests, the mink can also kill baby lambs.

Eventually, with a decline in membership, the Rabbit Society was wound up in 1992.

Mole catching. Another pest was the mole. Cecil was also the mole catcher and still fulfils this role on a private basis. Other mole catchers in the valley were David Martindale and Herbert Park. Mole catching is carried out with several different types of trap. The old wooden barrel kind has been replaced by the popular metal barrel trap, which can catch at either end or the pincer type. Some mole catchers use strychnine poison, mixed with worms.

David martindale, great-uncle

to Colin Park, who stayed

at South Low Farm. He was

an excellent mole catcher

This is placed in the underground runs. Mole catching requires skill, with the key to success being the ability to find a suitable underground run in which to set the trap. The catcher has to leave no unusual scent on the trap for the mole to detect as it has a very sensitive sense of smell. If it thinks anything is amiss it fills the trap with soil, to avoid being caught! In the past, moles were caught for their skins. When the moles had been caught, they would be skinned and stretched on a wooden plank, with six nails. When they were half dried, they were taken outside and the planks were set up against a wall, to dry the skins in the wind. When mink farming came into being the profit went out of moleskins.

Hunting has always been a well supported sport, particularly with the need for farmers to control foxes. Generally fox-hunting has been carried out on foot in the valley, except for the Oxenholme Stag Hounds. Hare coursing and otter hunting were also popular but nowadays only fox-hunting is practised. An extract from Edgar Park’s (Low Farm) diary from 1932 reads, “Went beating on Mosses today, which was favoured with fine weather. Got about 101 pheasants, 7 hares, 10 partridges, 2 woodcocks and 4 rabbits. There were 14 of us beating, including Ben, Bob and Walter Millburn”.

It is hard to imagine that the otter was once a common sight in the watercourses of Crosthwaite and Lyth and that a pack of hounds hunted them for sport. They were regarded as vermin. Now, along with badgers and many other species of animals and birds, they are a rare and protected species.

Setting a mink trap on the River Gilpin

(Daily Express)

Crosthwaite mill pond, used for

fishing and swimming!

Fishing A River Board Licence was required for fishing in the River Gilpin although many a lad has adopted a less orthodox approach and “tickled” trout. The favourite spot was the mill dam and weir. Bill, Harry and Tom Walling and John Wilson from Yews were all keen fishermen, always hoping for a salmon. Their record for one day’s fishing, a bag of 42 sea trout, was held by John Wilson! Dennis Inman, in his Recollections of a Lakeland Man, tells how he used to catch fish at Crosthwaite Mill. They had a place at the bottom of the “by wash”, where the water went to the mill or back into the river.

With the aid of a wooden box and a maize bag, they caught the fish left stranded when the sluice gates were operated. They collected as many as 90 sea trout at a time in this fashion but this did not go in the official record books! Salmon were caught by using the light from a stable lantern, to attract them.